I have referenced before educator Dr. Ruby K. Payne and her book, Bridges Out of Poverty, that helped me so much to understand the hidden rules associated with the three broad socio-economic classes. Another book of hers, A Framework for Understanding Poverty, was also helpful in developing my awareness of internal and external resources that people either have within them or that they have access to through others. After working with homeless people in a day counseling center and doing job readiness counseling, I began to see how valuable it can be to have a discussion about one’s “resources”. The resources Payne identifies in Chapter 1 of the “framework” are : financial, emotional, mental/cognitive, spiritual, physical, support systems, relationships/role models, knowledge of hidden rules, and language/formal register. Payne’s “resources” are focused on the things needed for educational interventions. Ours at Titus 2 are somewhat more narrowly focused on one’s awareness of her status in regard to particular life areas and the resources she possesses or needs to acquire in those life areas.

The self-evaluation process necessitates moving them away from the notion of money or material goods alone as one’s “resources” to thinking about skills, history, personality, attitudes, relationships, knowledge, and other intangibles as resources that can be brought to bear on one’s circumstances and motivation. It helps one identify strengths where resources are already in place and on which she can immediately begin to build and to also identify specific deficiencies that can be addressed through accessing community resources. As I have sat with individuals who have reached such a point in life that they can see little resourcefulness or resilience within them or around them, it is interesting to see how identifying intangible strengths and identifying specific deficiencies that can be addressed can shift their self-concept paradigm and their motivation when they begin to see themselves through another’s more objective eyes. Personal agency and executive decision-making can be re-engaged in individuals who have been pummeled by life-limiting dysfunctions into feeling they have no future and no hope. This is a cognitive exercise that requires one to review her past and present, looking for moments or seasons when life actually was “working”, and think about what was actually present that was making it work at that time. It can help facilitate the grieving component of the life recovery process, too, and move individuals beyond denial, shock, anger, and depression, into dealing with the reality of life as it is.

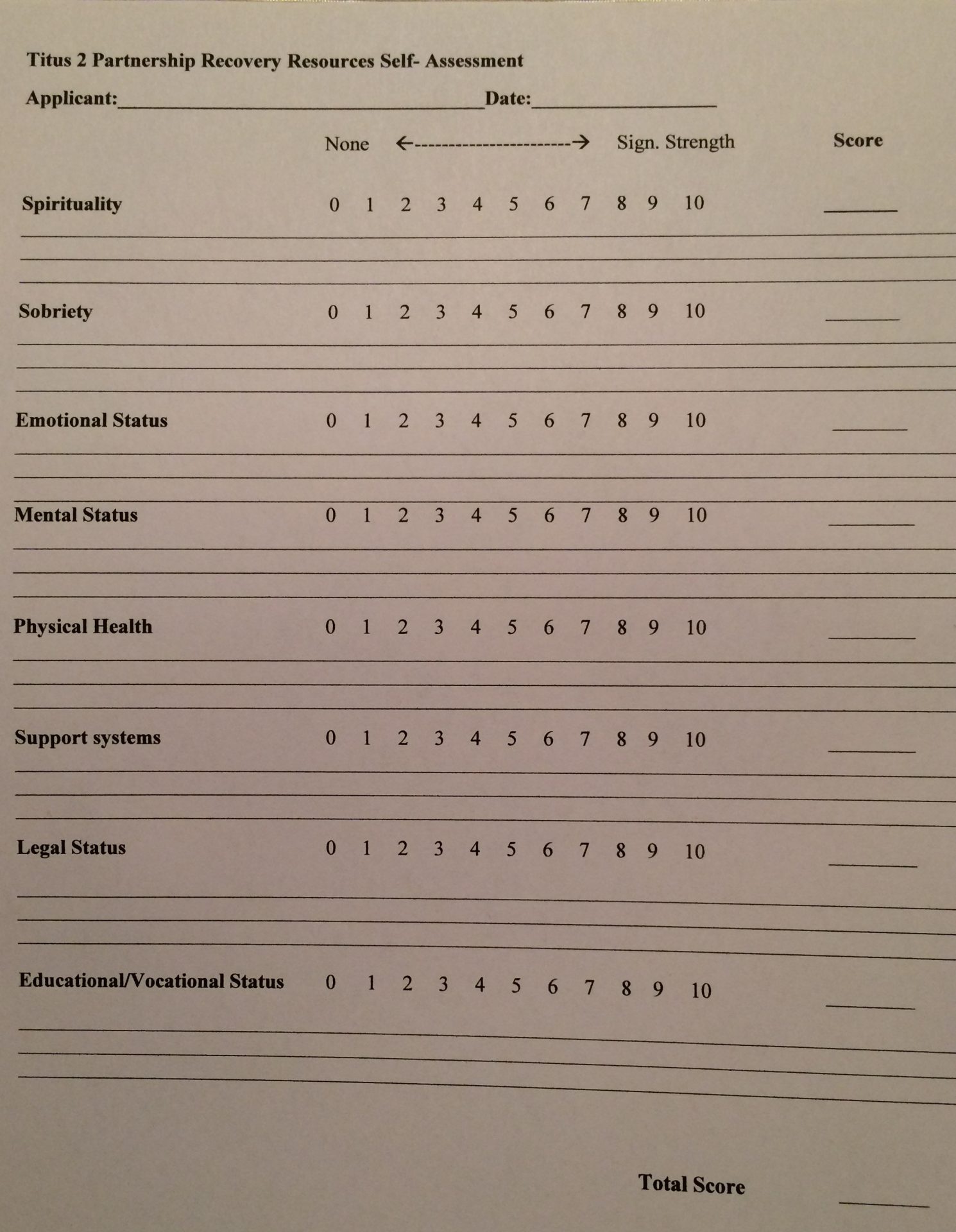

It led me over time to develop a Likert Scale self-evaluation for women with whom I work in life recovery. There are eight life areas in which they are prompted by a series of questions to rate themselves on a 0 to10 scale. A “0” score indicates “None or Not Applicable” in terms of the individual’s resources in that area. A “10” score indicates “Significant Strength” in that particular area. Obviously, few of my life recovery residency students have many, if any “10” scores or they wouldn’t be in life recovery residency. For most, anything at or above a “5” will be viewed as a notable strength for them at the point in which this is being undertaken.

The total maximum score of 80 provides a target toward which to work as one progresses through the program. Generally those with at least a score of 30-40 out of 80 can achieve significant growth and progress in recovery in the six month timeframe of our program. They can use the insights to set identifiable, realistic goals and plans for achieving them.

As I talk through some questions associated with each of the eight life areas, students are encouraged to self-score themselves on the scale. The list provided is not restrictive. We can go beyond those particular questions into areas like work ethics, sense of humor, diversity of knowledge, reading and language skills, extroverted conversational style, etc. It challenges them to think more objectively and realistically about themselves and their circumstances. It also helps trigger recognition of certain people, skills, or other internal or external resources they may have that they have not considered in the past as part of their “recovery capital”. With one young lady, realizing that she had some supportive family members still communicating with her, a middle class educational upbringing, no felonies, and a broad knowledge base about the community suddenly made her realize that she did have strengths and options. The idea of recovery resource “capital” that had nothing to do with money was an immediate epiphany for her. It might take time to re-engage some of it, but it was still there. Her sense of hope, self-agency and motivation began to be renewed in that discussion. She suddenly realized there were things she COULD begin doing now. It wasn’t a hopeless, lost-cause kind of situation in which she found herself. That paradigm shift would have eventually occurred anyway, I’m sure, as she began to feel more rested, safe, secure, and had the time to think things through. But the self-assessment crystallized some of those things more quickly…..for her and for me. We could develop a treatment plan together to capitalize on strengths immediately. We could also identify deficiencies that would require more time and strategic actions to address. It could direct us toward interests and skills for which we could access more training information, or support for her.

I offer these notes on prompting questions and the scale as a starting point for others who may be working with marginalized populations as a means of inspiring realistic and thoughtful conversations about where one sees herself, what she herself brings to the table in her recovery treatment plan, and how to begin moving forward. This is an XPS file. Click on it to view the 2 page document.

Recovery Resources Self- Assessment 8-2017

![MPj04389070000[1]_phixr](http://disciplerofself.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MPj043890700001_phixr.png)